The Kongouro from New Holland

photo: Achim Kukulies

Schrebergarten (allotment)

photo: Achim Kukulies

Persian garden

photo: Achim Kukulies

Conversation pit

photo: Achim Kukulies

Schrebergarten and stepping stones

photo: Achim Kukulies

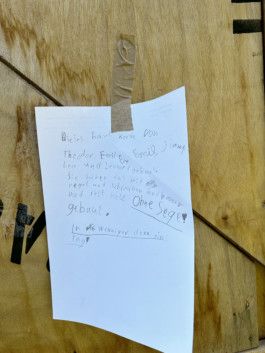

The hut

photo: Johannes Bendzulla

The hut

photo: Johannes Bendzulla

The hut

photo: Johannes Bendzulla

The Kongouro of New Holland

photo: Achim Kukulies

The baroque garden

photo: Achim Kukulies

Some Little Histories of Gardens and Playing is an installation that explores the garden as a projection of human desire — a site where spatial organization, power, and identity intersect. Gardens have long reflected how we imagine, shape, and assert control over the natural world: from the mythical Paradise or oasis, to the geometric logic of classical layouts, to the curated wilderness of the English landscape garden. Each form speaks to a distinct vision of society and the individual’s place within it.

As you move through the installation, your phone introduces an alternate spatial logic, guided by networks without borders — leading through digital walled gardens, formal enclosures, and conceptual terrains. How might our dreams of social organization shift in these reconfigured landscapes?

The installation continues an ongoing inquiry into the histories of zoological gardens, the great voyages of exploration, and the classification systems that emerged in their wake. These established modes of engaging with nature are placed in dialogue with alternative pedagogical models developed in the 19th and 20th centuries, which emphasized play as a foundational way of understanding the world.

Central to the installation is the reuse of The Interrupted Line (2021), a previous public artwork whose modular form now ‘frames’ a Persian garden, a Baroque parterre, a Schrebergarten (German allotment), and a low table inspired by both the Persian Korsi and the Japanese Kotatsu table.

The Persian garden follows the Chahar Bagh model, divided into four quadrants representing earth, fire, water, and air, a symbolic oasis sustained by sophisticated irrigation. By contrast, the Baroque parterre, also divided into four, expresses the Cartesian and Pythagorean logic of the early modern period. Its aesthetic, defined by control and symmetry, demands constant maintenance and excludes natural transformation over time.

A 3D-printed kangaroo stands in the parterre, painted in seven segmented colors that reflect its additive manufacturing process. The animal refers to George Stubbs’s 1772 painting The Kongouro from New Holland, commissioned by Joseph Banks and based not on a live model, but on sketches and an inflated skin brought back from Australia. Like the original image, this sculpture questions the veracity of representation and our often fragmentary knowledge of the natural world. It, too, was created not from a real specimen, but through verbal and written descriptions, a reconstruction based on incomplete information. Notably, Stubbs situated the animal within an English pastoral landscape rather than its native environment. In this installation, the kangaroo is placed in a baroque garden to echo and critically reflect on that original displacement.

The inclusion of the Schrebergarten bridges historical notions of gardens with spaces of play and communal use, leading toward the low table and platforms found at the heart of the installation.

Dr. Moritz Schreber, a 19th-century physician and social reformer, advocated for the creation of playgrounds and gardens to promote children’s health, family life, and education through outdoor play. Over time, these gardens evolved into vital urban resources, providing food security and social cohesion, especially during the two world wars.

In the 1950s, the devastation of war sparked a new vision for public space. Structuralist architects such as Aldo van Eyck reimagined the city as a network of human-centered environments. His more than 700 playgrounds throughout the Netherlands aimed to rebuild community life through the lens of the child’s experience. These ideas fueled the playground revolution of the 1960s and 70s — a lineage that informs the table at the center of this installation.

Surrounded by concrete platforms at varying heights, the table functions as a gathering place for talks, discussions, and community use throughout the duration of the exhibition.

The small garden hut, a familiar element in many allotments, was constructed from scrap wood in collaboration with local children. It is an homage to the Junk Playground (1943) in Emdrup, Denmark, designed by Carl Theodor Sørensen and John Bertelsen. Their radical idea to give children the tools and freedom to build their own environment is extended here as both a tribute and a living experiment.

Finally, the installation invites ongoing participation: local visitors are encouraged to care for the gardens by watering the plants, turning this space into a living and shared responsibility.